library(igraph)Network Data

Introduction

This introductory chapter will give a short explanation of key terminology and how network data can be represented. The larger part of the chapter is concerned with representing networks in R using igraph and how to construct or read network data.

After reading this chapter, you should have a basic understanding of what networks and network data is and how to create network objects in R using igraph.

What is a network?

In the context of social network analysis, a network is a conceptual and analytical construct to understand, visualize, and examine the (social) relationships and structures that emerge from the interactions among individuals, groups, organizations, or even entire societies. At its core, a network consists of nodes (which represent the actors, whether individuals or organizations) and edges (which signify the relationships or connections between these actors). These relationships can embody various types of interactions such as communication, friendship, professional ties, or social influence, among others.

Networks in the social sciences are tools for mapping and quantifying the patterns of social connections, helping to reveal the underlying dynamics of social cohesion, influence, and information flow within a community or society. Through the lens of network theory, analysts can explore how social structures influence behaviors, opportunities, and outcomes for individuals and groups, making it an invaluable approach in sociology, anthropology, political science, and many other disciplines that study social systems and interactions.

Network representations

There are several possible ways to express network data. All come with a set of advantages and disadvantages.

Adjacency Matrix

An adjacency matrix is a square matrix where the elements indicate whether pairs of vertices in the graph are adjacent or not—meaning, whether they are directly connected by an edge. If the graph has \(n\) vertices, the matrix \(A\) will be an \(n \times n\) matrix where the entry \(A_{ij}\) is \(1\) if there is an edge from vertex \(i\) to vertex \(j\), and \(0\) if there is no edge. In the case of weighted graphs the weight of the edge is used. This matrix is symmetric for undirected graphs, indicating that an edge is bidirectional.

Pros:

Simple Representation: It provides a straightforward and compact way to represent graphs, especially useful for dense graphs where many or most pairs of vertices are connected.

Efficient for Edge Lookups: Checking whether an edge exists between two vertices can be done in constant time, making it efficient for operations that require frequent edge lookups.

Easy Implementation of Algorithms: Many graph algorithms can be easily implemented using adjacency matrices, making it a preferred choice for certain computational tasks.

Cons:

Space Inefficiency: For sparse graphs, where the number of edges is much less than the square of the number of vertices, an adjacency matrix uses a lot of memory to represent a relatively small number of edges.

Poor Scalability: As the number of vertices grows, the size of the matrix grows quadratically, which can quickly become impractical for large graphs.

Edge List

An edge list is a matrix where each row indicates an edge. In an undirected graph, an edge is represented by a pair \((i,j)\), indicating a connection between vertices \(i\) and \(j\). For directed graphs, the order of the vertices in each pair denotes the direction of the edge, from the first vertex to the second. In weighted graphs, a third column can be added to each pair to represent the weight of the edge.

Pros:

Space Efficiency for Sparse Graphs: Edge lists are particularly space-efficient for representing sparse graphs where the number of edges is much lower than the square of the number of vertices, as they only store the existing edges.

Simplicity: The structure is straightforward and easy to understand, making it suitable for simple graph operations and for initial graph representation before processing.

Cons:

Inefficient for Edge Lookups: Checking whether an edge exists between two specific vertices can be time-consuming, as it may require scanning through the entire list, leading to an operation that is linear in the number of edges.

Inefficiency in Graph Operations: Operations like finding all vertices adjacent to a given vertex or checking for connectivity between vertices can be inefficient compared to other representations like adjacency matrices or adjacency lists, especially for dense graphs.

Less Suitable for Dense Graphs: As the number of edges grows, the edge list can become large and less efficient in terms of both space and operation time compared to an adjacency matrix for dense graphs, where the number of edges is close to the maximum possible number of edges.

Adjacency List

An adjacency list is a collection of lists, with each list corresponding to the set of adjacent vertices of a given vertex. This means that for every vertex \(i\) in the graph, there is an associated list that contains all the vertices \(j\) to which \(i\) is directly connected.

Pros:

Space Efficiency: Adjacency lists are more space-efficient than adjacency matrices in sparse graphs, as they only store information about the actual connections.

Scalability: This representation scales better with the number of edges, especially for graphs where the number of edges is far less than the square of the number of vertices.

Efficiency in Graph Traversal: For operations like graph traversal or finding all neighbors of a vertex, adjacency lists provide more efficient operations compared to adjacency matrices, particularly in sparse graphs.

Cons:

Edge Lookups: Checking whether an edge exists between two specific vertices can be less efficient than with an adjacency matrix, as it may require traversing a list of neighbors.

Variable Edge Access Time: The time to access a specific edge or to check for its existence can vary depending on the degree of the vertices involved, leading to potentially inefficient operations in certain scenarios.

Higher Complexity for Dense Graphs: In very dense graphs, where the number of edges approaches the number of vertex pairs, adjacency lists can become less efficient in terms of space and time compared to adjacency matrices, due to the overhead of storing a list for each vertex.

Importing Network Data

Foreign Formats

igraph can deal with many different foreign network formats with the function read_graph. (The rgexf package can be used to import Gephi files.)

read_graph(

file,

format = c(

"edgelist",

"pajek",

"ncol",

"lgl",

"graphml",

"dimacs",

"graphdb",

"gml",

"dl"

),

...

)If your network data is in one of the above formats you will find it easy to import your network.

Nodes, Edges, and Attributes

If your data is not in a network file format, you will need one of the following functions to turn raw network data into an igraph object: graph_from_edgelist(), graph_from_adjacency_matrix(), graph_from_adj_list(), or graph_from_data_frame().

Before using these functions, however, you still need to get the raw data into R. The concrete procedure depends on the file format. If your data is stored as an excel spreadsheet, you need additional packages. If you are familiar with the tidyverse, you can use the readxl package. Other options are, e.g. the xlsx package.

Most network data you’ll find is in a plain text format (csv or tsv), either as an edgelist or adjacency matrix. To read in such data, you can use base R’s read.table().

Make sure you check the following before trying to load a file: Does it contain a header (e.g. row/column names of an adjacency matrix)? How are values delimited (comma, whitespace or tab)? This is important to set the parameters header, sep to read the data properly.

Networks in igraph

Below, we represent friendship relations between Bob, Ann, and Steve as a matrix and an edgelist.

# adjacency matrix

A <- matrix(

c(0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0),

nrow = 3,

ncol = 3,

byrow = TRUE

)

rownames(A) <- colnames(A) <- c("Bob", "Ann", "Steve")

A Bob Ann Steve

Bob 0 1 1

Ann 1 0 1

Steve 1 1 0# edgelist

el <- matrix(

c("Bob", "Ann", "Bob", "Steve", "Ann", "Steve"),

nrow = 3,

ncol = 2,

byrow = TRUE

)

el [,1] [,2]

[1,] "Bob" "Ann"

[2,] "Bob" "Steve"

[3,] "Ann" "Steve"Once we have defined an edgelist or an adjacency matrix, we can turn them into igraph objects as follows.

g1 <- graph_from_adjacency_matrix(A, mode = "undirected", diag = FALSE)

g2 <- graph_from_edgelist(el, directed = FALSE)

# g1 and g2 are the same graph so only printing g1

g1IGRAPH de86b43 UN-- 3 3 --

+ attr: name (v/c)

+ edges from de86b43 (vertex names):

[1] Bob--Ann Bob--Steve Ann--SteveThe printed summary shows some general descriptives of the graph. The string “UN–” in the first line indicates that the network is Undirected (D for directed graphs) and has a Name attribute (we named the nodes Bob, Ann, and Steve). The third and forth character are W, if there is a edge weight attribute, and B if the network is bipartite (there exists a node attribute “type”). The following number indicate the number of nodes and edges. The second line lists all graph, node and edge variables. Here, we only have a node attribute “name”.

The conversion from edgelist/adjacency matrix into an igraph object is quite straightforward. The only difficulty is setting the parameters correctly (Is the network directed or not?), especially for edgelists where it may not immediately be obvious if the network is directed or not.

Import via snahelper

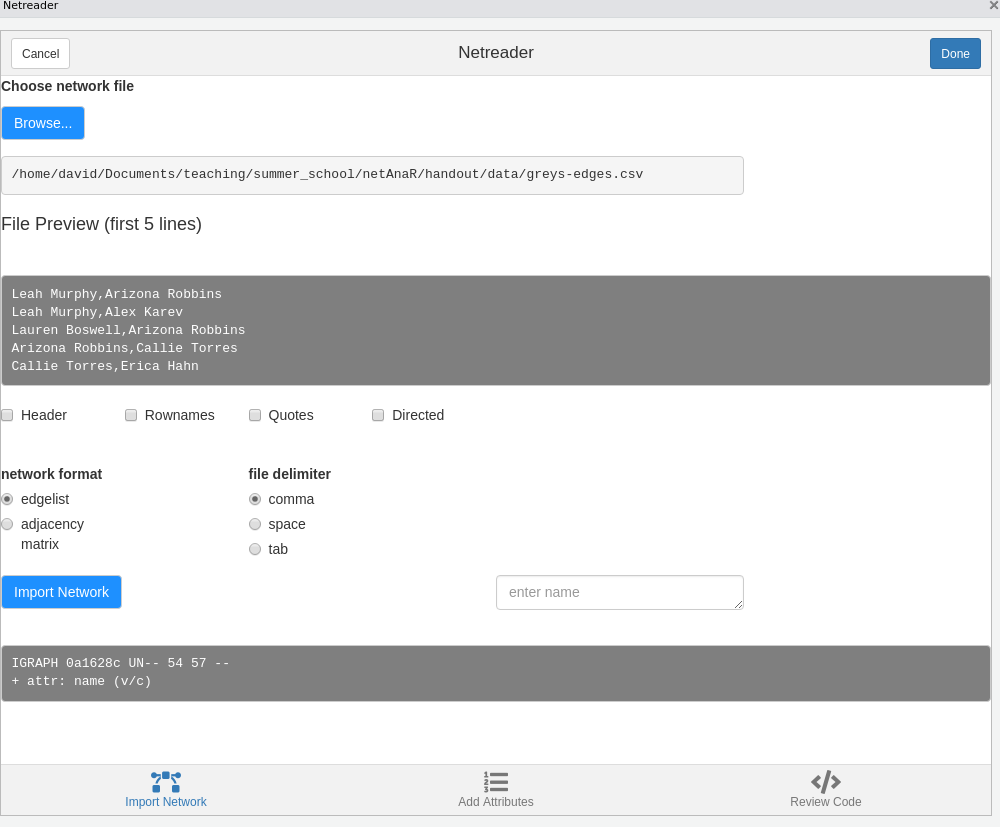

The R package snahelper implements several Addins for RStudio that facilitate working with network data by providing a GUI for various tasks. One of these is the Netreader which allows to import network data.

The first two tabs allow you to import raw data (edges and attributes). Make sure to specify file delimiters, etc. according to the shown preview.

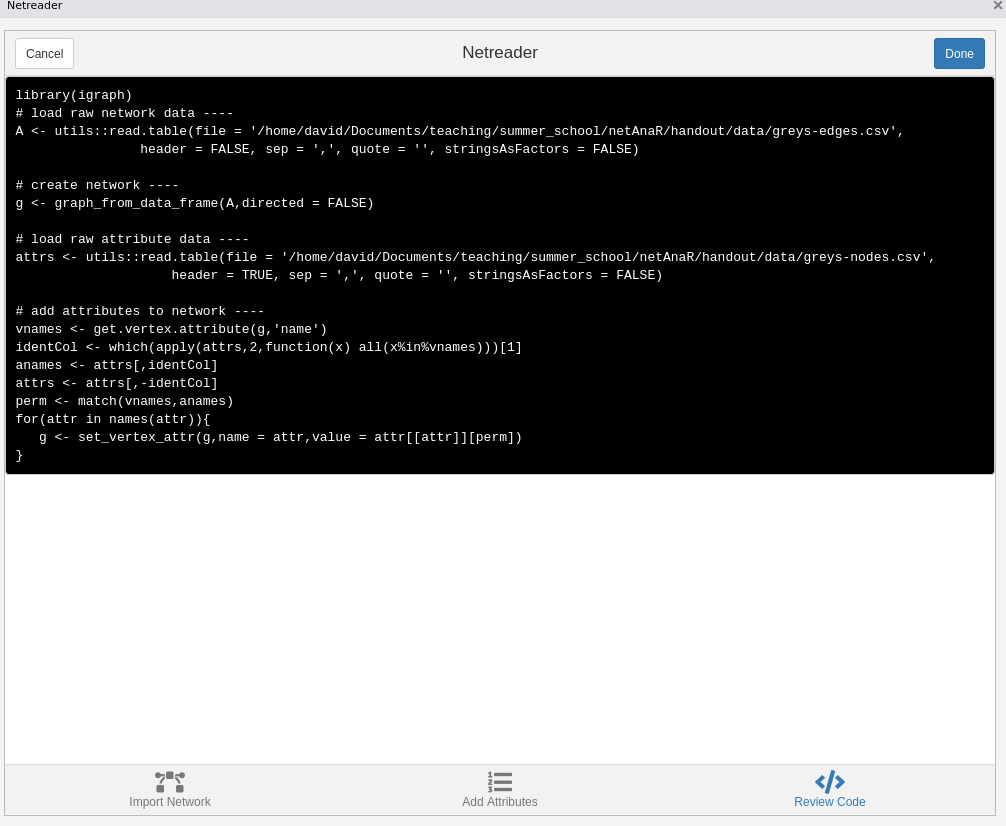

Using the Netreader should comes with a learning effect (hopefully). The last tab shows the R code to produce the network with the chosen data without using the Addin.

The network will be saved in your global environment once you click “Done”.

Scientific reading

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications.

Scott, J. (2012). What is Social Network Analysis? Bloomsbury Academic.